Analysis of the results of the first three monitoring campaigns

Have you ever heard of the Anthropocene? It's a term currently being debated to define a new geological epoch. In other words, the era when mankind is in control of significant changes to the Earth's systems! Sounds good, doesn't it? Or maybe not! Whatever the case, climate change has been at the heart of the concept ever since it was first mentioned publicly in 1988 by Professor James Hansen.1. In this unprecedented context, forests, which can also play a role in mitigating the phenomenon, are suffering. Forest ecosystems, which are particularly important for biodiversity and wood production, are in decline, which is a cause for concern for foresters on both sides of the planet. For the Royal Forestry Society of Belgium, it is vital to do more to promote sustainable forestry, to ensure the long-term survival of our forests. The project Trees For Future is just one of the many initiatives set up by the ASBL to help forests adapt to climate change. Launched in 2018, Trees for Future aims to broaden the range of tree species and provenances available to forest managers, in order to strengthen the resilience of forests.

Summary

The project Trees for Future is testing different provenances and species in a network of experimental plots across the country. This year, a comparative analysis of the first three years of monitoring the plantations was carried out (survival rate, state of health and growth of the seedlings). Trees For Future is still in its infancy and has produced some promising initial results. Current results are positive in the vast majority of experimental plots. Most of the damage and planting failures are man-made and can therefore be resolved. Health surveys show nothing alarming or unexpected. Some tree species are showing encouraging growth, which needs to be confirmed in the coming years. From the point of view of drought and heatwave, the plantations responded well to 2022 and showed minimal losses, except for the metasequoia and Byzantine hazel. Late frosts affected a number of species, but without any major damage. The Trees for Future aims to test different provenances and species in forests within a network of experimental plots spread throughout the country.

The aim is to evaluate these species and provenances according to various criteria:

- adaptation to current and future climates;

- resistance to pests (insects) and pathogens (diseases, fungi) ;

- wood productivity and quality for timber production ;

- the effect on biodiversity (carrying capacity of flora and fauna and risk of invasions).

OUR PARTNERS

THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

Trees for Future is carried out in close collaboration with a scientific committee. This rigorous and experienced committee is responsible for selecting the species and provenances to be tested. Together, we have drawn up and validated the installation protocol and the monitoring protocol. This committee will also help analyse the data collected.

It is made up of :

- several Belgian universities (KULeuven, UCLouvain and ULiège);

- the Department for the Study of the Natural and Agricultural Environment (DEMNA) and its Flemish counterpart the’Instituut voor Natuur en Bosonderzoek (INBO) ;

- the Department of Nature and Forests (DNF), via the Comptoir Forestier (Walloon forest seed collection and sorting service).

NURSERYMEN

The plants are produced from seeds purchased in the countries of origin. Thanks to our partnership with Belgian and French nurseries, we can rely on their expertise to supply us with quality plants.

THE NFB

SRFB was a partner in the FuturForEst which took place between 2019 and 2023. It brought together players from the public (ONF and association of forest communities) and private (CNPF) forest sectors. More than a play on words, FuturForEst The aim of the project was to plant islands of future trees of 10 different new species as part of the process of adapting the forests of the Grand Est region to climate change. The planting work took place between November 2020 and January 2023. It will have resulted in the installation of 70 systems in public and private forests. This project was directly linked to our Trees for Future and both have benefited from the experience gained with new species on either side of the Franco-Belgian border. The results of the project are more than positive, and the collaboration will continue beyond the end of the project, with two sites being monitored jointly by the ONF and the SRFB.

THE VOLUNTEERS

Scientific monitoring of the plantations requires numerous measurements and observations in the field. For this reason, we have recruited a team of volunteer foresters who have been specifically trained to collect information in the field in strict compliance with the scientific protocol.

FOREST OWNERS

Many forest owners (both private and public) generously make plots of woodland available to us and look after them.

THE PARTNERS

The project operates mainly on private funds. It only exists thanks to the generosity of citizens who are sensitive to forestry issues and committed companies.

THE SYSTEM

To contribute to this research into the adaptive management of Belgian forests, 24 species (46 provenances) are currently being tested, including 13 softwoods and 11 hardwoods (Tables 1 and 2). 187 experimental plots of 0.2 ha, spread over 46 sites, host the system. The trees were planted either in the open (400 plants of one provenance, 2 x 2.5 m) or in cells (minimum 5 cells of 25 plants, 1 x 1 m per provenance, spaced 12-15 metres apart). During the next planting season (2023-2024), four new softwood species should be planted: Cephalonia fir (Abies cephalonica), Serbian spruce (Picea omorika), Oriental spruce (Picea orientalis) and Macedonian pine (Pinus peuce).

In order to assess the establishment, behaviour and adaptation of tree species to different biotic and abiotic factors2, A follow-up survey is carried out in the spring following planting, as well as an autumn survey, which is repeated every year. These measurements are carried out with the help of a team of 30 volunteers. During the post-planting survey, the quality of the planting and the health of the plants are assessed by observing 50 individuals per plot. In autumn, 50 plants, identified in a permanent plot, are measured for height and diameter growth, health and conformation (forks, curvature, etc.).

Note: For plots planted in cells, 9 central plants from each cell are monitored. An experimental plot comprises 5 to 6 cells.

RESULTS

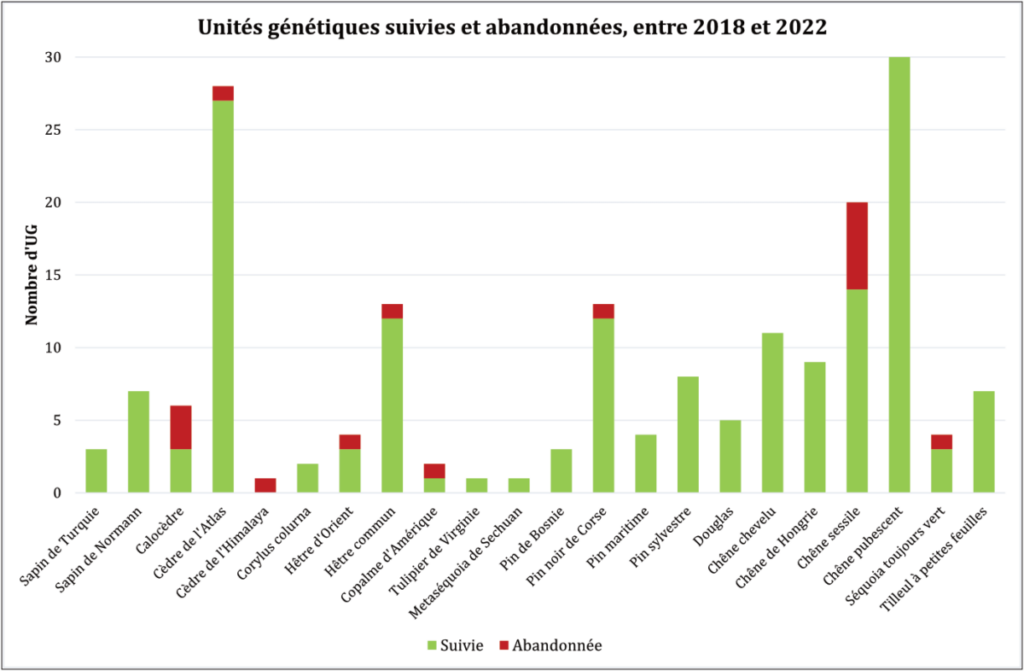

This year, a comparison of the first three years of monitoring was carried out. We begin by looking at Figure 3 (next page). It compares the number of experimental plots (UG) for which the spring recovery rates were too low to consider installing a permanent plot for autumn monitoring (abandoned) with the number of experimental plots monitored. First of all, it should be noted that the abandoned plots were in the minority, as the vast majority of the plots recovered well after planting.

These abandonments were the result of identified health problems (e.g. hylobes for Atlas cedars), problems storing seedlings before planting (e.g. sessile oak) and problems with competing vegetation associated with clearance problems (e.g. Himalayan cedar, calocedar). Errors in the planting scheme are also at the root of some abandonments (e.g. mixing of provenances and species within an experimental plot).

Redwoods planted before 2021-2022 have suffered high losses. The deaths are mainly associated with the species' sensitivity to the cold, dry east winds in spring. It is clear that lateral shelter is essential for successful planting. When replanting, the use of individual sheaths reduced the impact of these winds.

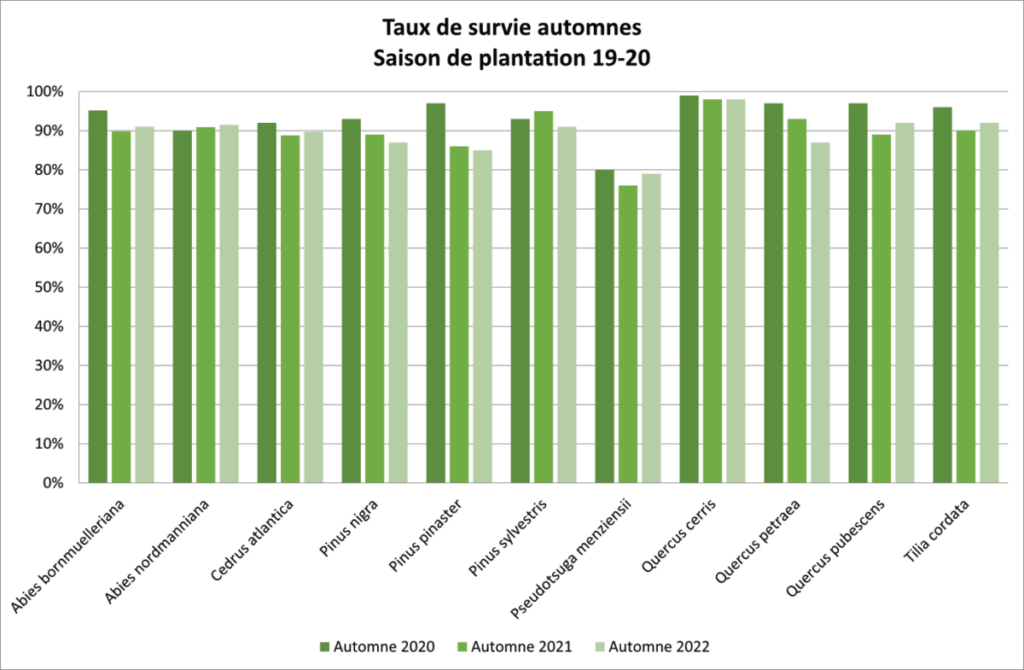

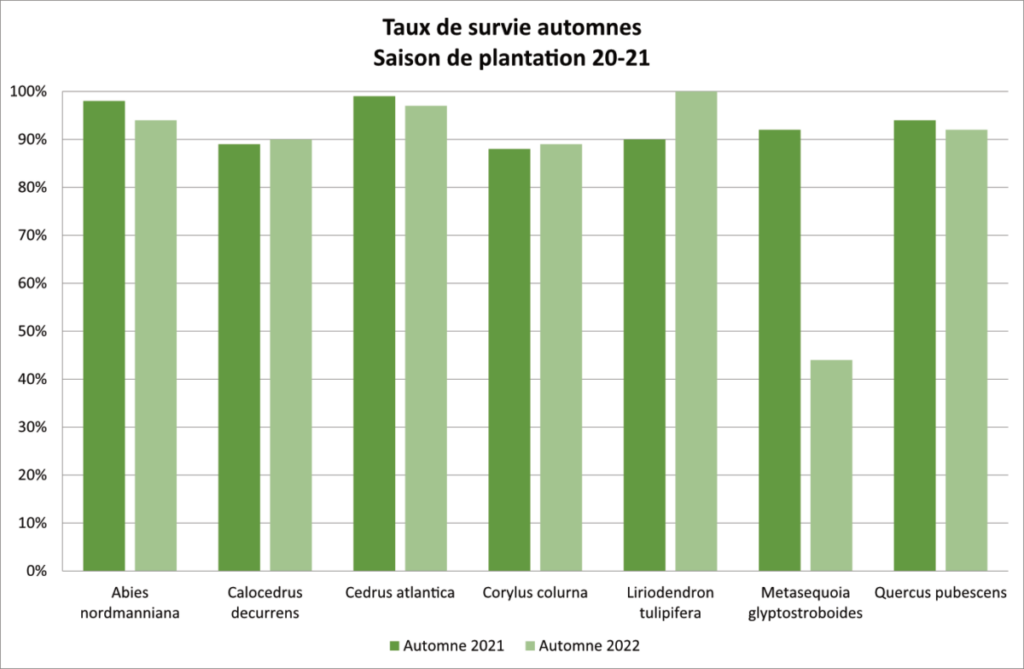

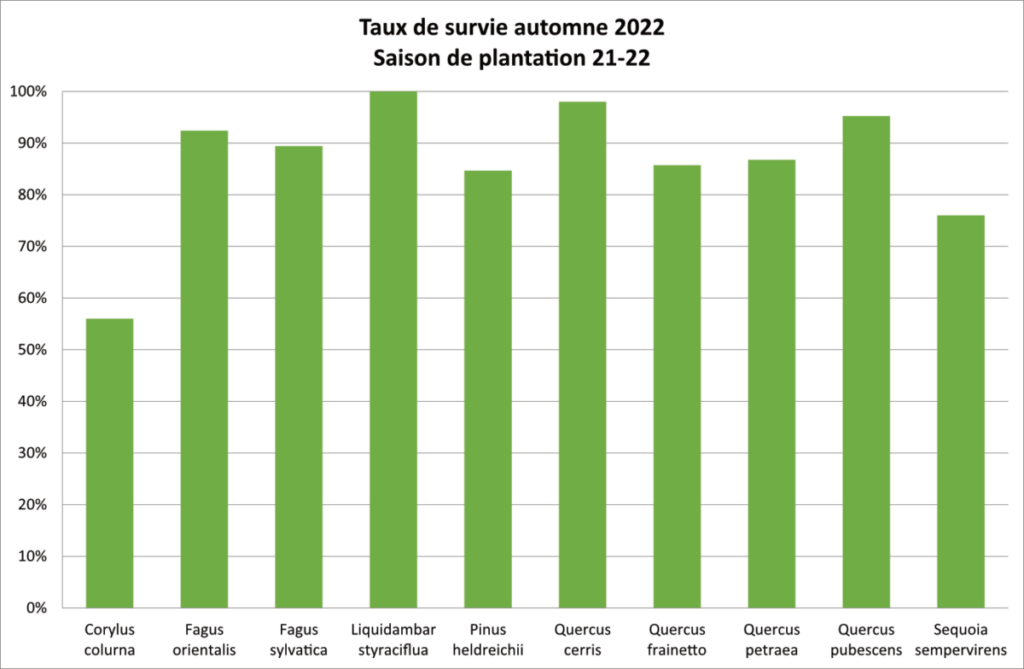

Secondly, we will analyse Figures 4 to 6, which show the average survival rates, by species, measured during autumn monitoring for three planting seasons. Only plots that are still being monitored today are taken into account (those that were abandoned along the way are not included (see Figure 1)). These figures show very good overall survival rates. It should be noted that, in some cases, survival rates are increasing over time. There are two explanations for this: false deaths (resprouting at the collar the year after the observation, plant not found but present, etc.), and some reseeding.

Let's take a closer look at the results for a few species. Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is the species from the 2019-2020 planting season with the worst survival rate (Figure 4). It was planted on difficult sites, where it suffered from a restrictive water regime due to the dry climate and shallow soil. Among the species planted in 2020-2021, it is the metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), which stands out unfavourably, with a mortality rate falling to over 50 % in 2022 (Figure 5). Highly sensitive to water shortage3, A large part of the mortality of metasequoia is due to the droughts of 2022. For the 2021-2022 planting season, Byzantine hazel (Corylus colurna) has the lowest survival rate (Figure 6). The planting of this species was followed by a period of intense drought. Being a drought-sensitive species during the first ten years, it is possible that the mortality rate may be linked to this.

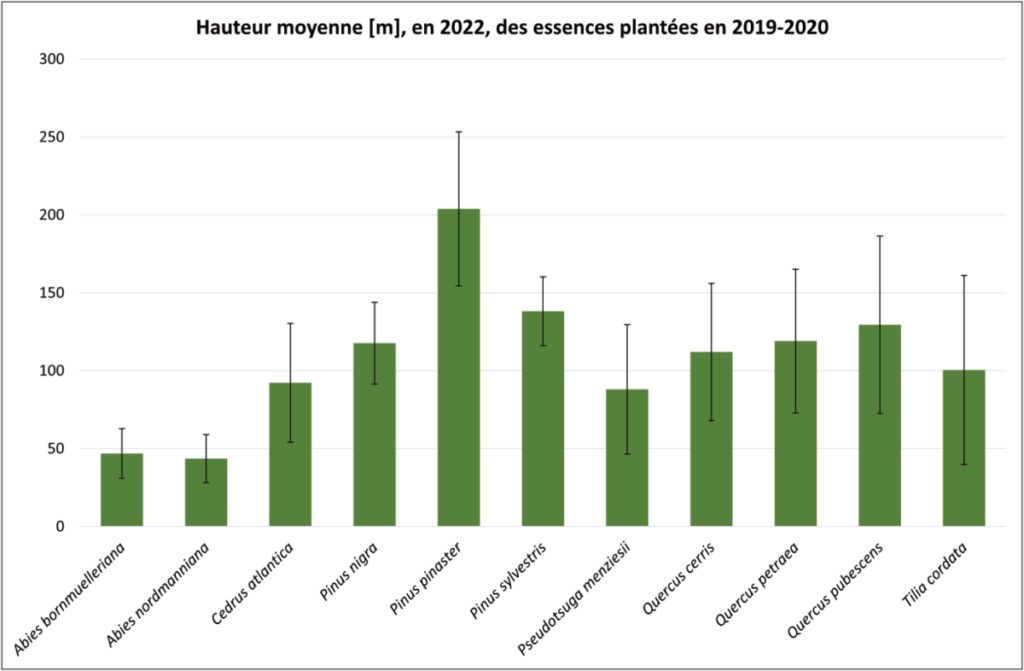

In addition to survival rates, the monitoring also enabled us to take stock of plant growth. Graph 7 compares the average height in 2022 of the species planted in 2019-2020. The first observation concerns the slow growth of firs (Abies). Pines, on the other hand, are the species for which the best growth has been recorded. Generally speaking, analysis of the growth in height and diameter of seedlings has shown that broadleaved trees were more sensitive to the drought of 2021 than softwoods. However, the standard deviations (black line) for the heights of each species show that there is a wide disparity depending on the site, health and planting conditions, but also between different provenances within the same species. It will be possible to analyse these data more widely in a few years' time.

| French name | Prov. | Total UG | 18-19 | 19-20 | 20-21 | 21-22 | 22-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkish fir | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Nordmann fir | 2 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Calochedron | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Atlas Cedar | 4 | 29 | 3 | 20 | 4 | 2 | |

| Himalayan Cedar | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Arizona cypress | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Metasequoia | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Bosnian pine | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Black pine | 3 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Maritime pine | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Scots pine | 2 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Douglas | 2 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Evergreen redwood | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Table 1: Softwood species. UG: genetic unit, i.e. experimental plot (the 22-23 planting season is given here as an indication; we will have to wait until autumn 2023 for an initial analysis of monitoring results).

| French name | Prov. | Total UG | 18-19 | 19-20 | 20-21 | 21-22 | 22-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corsican Alder | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Byzantine Hazel | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Oriental beech | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Common beech | 2 | 13 | 12 | 1 | |||

| American copalm | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tulip tree | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Hairy oak | 3 | 11 | 8 | 3 | |||

| Hungarian oak | 2 | 12 | 9 | 3 | |||

| Sessile oak | 3 | 14 | 7 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Pubescent oak | 6 | 31 | 14 | 2 | 14 | 1 | |

| Small-leaved lime | 3 | 7 | 7 |

Table 2: Hardwood species. UG: genetic unit, i.e. experimental plot (the 22-23 planting season is given here as an indication; we will have to wait until autumn 2023 for an initial analysis of monitoring results).

PLANT HEALTH

Health monitoring is carried out in partnership with the Observatoire wallon de la santé des forêts (OWSF). Generally speaking, the health surveys are satisfactory. The problems and symptoms observed cause growth delays, but rarely lead to the death of the tree.

ABIOTIC PROBLEMS

Many of the problems reported are associated with silvicultural damage. The plants are small when planted and require a lot of clearing, which can cause injury to young trees. Most of the plants installed are produced in France, in buckets that are ready after 1 year in the nursery. While pots have a number of advantages (better recovery and less planting stress, good growth from the first year, the possibility of planting them very early in the autumn to ensure rooting before spring, etc.), the plants are small, measuring just 15 to 20 cm. In situations of vigorous competition, ensuring they have access to light is a real challenge. There is a high risk of losing them through lack of clearance (see above: abandonment of Himalayan cedar and calocedar plots) or of cutting them inadvertently. Placing bamboo at the foot of each plant allows the plants to be seen and makes clearing easier.

Among the other problems noted, frost damage is notable in certain species. For example, all the American copalm (liquidambar styraciflua) was affected by the spring frost.

This climatic hazard did not result in mortality, but delayed growth and a greater need for training pruning. The other species for which frost damage was observed were Nordmann fir (Abies nordmanniana), Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), holm oak (Quercus cerris), sessile oak (Quercus petraea), downy oak (Quercus pubescens) and small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata). It is interesting to note that Nordmann fir has also been affected by this problem, but that it has never been recorded on Turkish fir (Abies bornmuelleriana).

According to our records, the drought of 2022 appears to have done little damage. The difficulty with abiotic hazards such as drought is that the symptoms are not very specific and can be confused with a whole range of different problems (planting stress, compacted soil, heatwave, deficiencies, other biotic problems not identified with certainty, etc.). The drought of 2022 will certainly have had an impact on the growth of certain species, but caused little mortality, except for metasequoias and Byzantine hazel (see figure 5).

BIOTIC PROBLEMS

With 25 % of sessile oaks (Quercus petraea) and 12 % pubescents (Quercus pubescens) affected by powdery mildew, these two species are the most severely attacked by the fungus, in comparison with hairy oak (Quercus cerris) and Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto).

In previous years, another problem was recorded: the pine false webworm, a hymenoptera. In 2020, 63 individuals affected by the insect were recorded, as well as 23 individuals in 2021. In 2022... zero. No pine bark beetles were recorded during the autumn 2022 survey. There are two possible reasons for this sudden change. Firstly, it may well have been present, but not identified. However, it is possible that it was present but not identified,

the insect cycle includes the likelihood of diapause4 for two or three years. The year 2022 could be in this stage of the insect's cycle, which would explain its absence. The impact of this insect on the forest is relatively low. However, defoliation of very young plants can weaken them. Plants over 5 years old are very rarely affected.5.

CONCLUSION

The project Trees for Future reflects a desire to ensure the sustainability and resilience of Belgium's forests. SRFB members and volunteers are working to propose a range of solutions to climate change.

Forestry is a management science that is often applied over the long term. Decisions taken today will only have an effect in several years, or even decades. So we need to be patient before we can draw categorical conclusions from the various experiments.

Trees for Future is still in its infancy and is showing promising initial results. Various species of one or more provenances (see tables 1 and 2) have been planted on sites with contrasting characteristics. Current results are positive in the vast majority of experimental plots.

Much of the damage and failure during planting is man-made and can therefore be remedied. The small size of the plants is a major limiting factor for successful planting (discouragement in the face of clearing) which requires a strategy to be mitigated (solutions to reduce the risks at the outset, work to be carried out in the plantations). The health surveys show nothing alarming or unexpected. Some species are showing encouraging growth, which needs to be confirmed in the coming years.

The choice of species to be tested in Trees for Future is not easy. One of the major difficulties is finding species that are resistant to drought and heatwaves, but that can also withstand the harsh winters and frosts (late or early) that will persist in our regions. A second difficulty is finding the right supplies.

in seeds and seedlings, as few, if any, of these species are produced in Belgium. The choice of species finally selected is therefore also conditioned by the possibility of obtaining them in sufficient quantity and quality.

In terms of drought and heatwave, the plantations responded well to 2022, with minimal losses, except for the metasequoia and Byzantine hazel.

The late frosts affected a number of species, but not seriously, and their susceptibility to this phenomenon at the juvenile stage is not surprising. Pruning will nevertheless be necessary for several of these species.

by Lola Badalamenti*, Julie Losseau** and Nicolas Dassonville**

* Trainee at the Royal Forestry Society of Belgium

** Trees for Future project leaders

- Richard A. Kerr, «Hansen vs. the World on the Greenhouse Threat», Science 244, no 4908 (2 June 1989): 1041-43, https:\/\/srfb.be//srfb.be//doi.org/10.1126/science.244.4908.1041.

- A biotic factor is a living factor (game, fungi, weeds, etc.), whereas an abiotic factor is a non-living factor (drought, storm, frost, deficiency, etc.).

- The metasequoia was not included in the plan, but an opportunity to plant it arose (plants available) and one of our members told us of his interest in this species. We therefore included it in the project.

- Temporary halt to development.

- Source : http://ephytia.inra.fr/